AN • TI • PRE • NEUR [AN-TEE-PRUH-NUR] Noun

1: A new breed of caring, sharing entrepreneurs who focus on marketing with a mission.

2: A person who is pro-business, but anti-big-company, preferring local, sustainable enterprises that balance work/home life.

3: Entrepreneurial activists seeking to transform capitalism into a positive grassroots phenomenon.

Antipreneurs, like entrepreneurs, are business-minded professionals. The difference? Antipreneurs view entrepreneurs as part of the problem: embracing everything that’s considered wrong with big business. They see themselves as more socially evolved than the typical entrepreneur. Thus, the more the capitalist boat is rocked, the more fulfilled the antipreneur becomes at the size of the waves they’ve helped create.

Although not yet officially recognized by Merriam-Webster, the term antipreneur is certainly creating buzz due to its perceived affront to capitalism. Should we fear antipreneurs or embrace them? Are their tactics productive or destructive? You be the judge.

Antipreneur = Anti-Advertising & Anti-Brand?

Although it’s been said that antipreneurs are anti-advertising, the truth is that they prefer to create awareness outside the realm of traditional advertising. They favor non-traditional measures such as word-of-mouth and social networking to spread the word about their products. Antipreneurs feel that these methods are more organic, grassroots ways to sell products.

Although it’s been said that antipreneurs are anti-advertising, the truth is that they prefer to create awareness outside the realm of traditional advertising. They favor non-traditional measures such as word-of-mouth and social networking to spread the word about their products. Antipreneurs feel that these methods are more organic, grassroots ways to sell products.

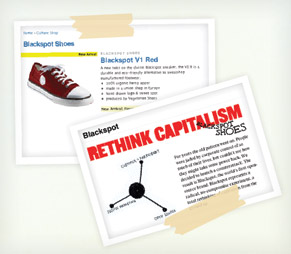

Ironically, some companies that tout themselves as anti-brand somehow appear virtually obsessed with the brands of large companies. Take Blackspot Shoes, for example. In 2003, Blackspot was founded on the premise of “unswooshing” Nike due to its labor practices (not to mention their purported bitterness that Nike’s aggressive advertising techniques have made high-priced tennis shoes a necessity among American teens).

Blackspot sells sneakers, curiously similar to Chuck Taylors, made of organic and biodegradable material. In lieu of the Converse logo, Blackspot has substituted a hand-painted white circular “anti-logo” in its place to suggest the obliteration of branding. Despite the fact that the logo is considered by Blackspot to be an “anti-logo” or “unlogo,” it still is, in essence, their brand.

To drive home the point of social consciousness, owners of Blackspot shoes are named automatic shareholders in The Blackspot Anticorporation — complete with a shareholder certificate in the shoebox and a password allowing the owner a voice in how the business will be run. As a result of their efforts, over 30,000 pairs of $100 Blackspots have been sold to date and the company’s founder claims victory in cutting into Nike’s market share.

Another U.S. antipreneur, known as No Sweat, ensures 100% American-made, sweatshop-free shopping — complete with full disclosure. Based in West Newton, Mass., No Sweat claims to be the first open source apparel manufacturer in the world. Their goal is to change an industry by targeting the workers’ rights market.

Another U.S. antipreneur, known as No Sweat, ensures 100% American-made, sweatshop-free shopping — complete with full disclosure. Based in West Newton, Mass., No Sweat claims to be the first open source apparel manufacturer in the world. Their goal is to change an industry by targeting the workers’ rights market.

The Antipreneur in All of Us

Everyone loves a good cause. And antipreneurs know it. By capitalizing on corporate cynicism and promoting a better world, antipreneurs are becoming masters at influencing purchasing decisions.

A study by the American Marketing Association (AMA) determined that:

- One of every three consumers stated they would be more likely to purchase a product if they knew that a certain percentage of the purchase price would be donated to a cause.

- Individuals ages 18-24 and women are most likely to purchase a product connected to cause-related marketing.

Love ’em or hate ’em, antipreneurs represent a trend poised to change the American business landscape by showing large corporations how corporate responsibility can be good for business. And we should all be listening.

IS THIS REALLY ANYTHING NEW?

Corporate social responsibility has been a component of most organizations’ marketing strategies for decades, either proactively or in response to crises or negative publicity. Practices have evolved from charitable and community involvement to the promotion of fair labor and sourcing practices, environmental sustainability and lower energy usage. Admittedly, some of these efforts have been perceived by the public as less than sincere (for example, Big Oil touting its “green” record) but nonetheless, antipreneurs are not the first.

They’re also not the first to try to balance social activism and making a profit. Early capitalist economists argued that the only responsibility of business was to maximize returns to shareholders and that using resources for anything else was a hindrance to free trade. But companies that utilize corporate social responsibility as a major element in their branding recognize that the customer passion and employee engagement they’ve created has value. Often rewarded, by the way, with a premium price point — for example, Starbucks or Whole Foods.

So, is there anything new from — antipreneurs? Maybe. Most attempts to use corporate social responsibility as a branding element are designed to make consumers and employees feel good about themselves by aligning with their values. Antipreneurs seem to want to create stress or contradiction in their consumers’ minds, forcing a decision — through their anti-branded products and non-logos — away from a “bad guy” brand to their “good guy” brand.

One Comment